reflections on how use and value intersect and change over time

* essays in the form of imagined narratives carry a light yellow background

I make my way to the river, bow and arrows in hand. These flat points of iron are simple but get the job done. A sudden glint catches my eye: a sharp small point, just the length of my pinky finger. How did this get here? Perhaps another hunter’s loss? I grab it – and wince. Three ridges around, curved barbs with sharp ends like the pin of a fibula: I’ve never seen an arrow like this. This is the work of a master smith.

The rising sun illuminates the river’s edge. I attempt to insert my new find into one of my wooden shafts but its short tang splinters the wood so I tie it in the usual way instead. As I crouch in the shrubbery, a doe approaches. I nock my arrow, draw a breath, and release. The arrow flies true, thanks to its narrow form and crisp lines. But when I reach my prey, I discover my new find is hard to release: it clings strongly to the animal’s insides. This is no ordinary point. It seems made to pierce armor and cling to flesh. Perhaps it was a witness to some past battle here? I shiver at the thought of encountering such a weapon, one that would guarantee death in an unshakable grasp.[1]

[1] Merker, “The Objects of Metal,” TA II ii, p. 257.

A short sniffle escapes from a bundle of blankets as I pass by in the darkness. One of the children must have had a nightmare. I reach for the lamp with a sigh, making a mental note to refill the oil in the morning. Thankfully, the woven wick seems almost endless — I can’t remember the last time I had to replace it.[1] Half asleep, I shuffle towards her with the lamp cupped snugly in the palm of my hand, glad its closed top protects me from spilling the oil in my exhausted state. It has been a long day, and I want nothing more than to sleep peacefully before another day of work.

The lamp’s soft glow comforts both of us. It is just enough light to let me see the the red laurel wreaths adorning the top.[2] When I picked it out from the hundreds piled in baskets at the local market, the merchant told me it had been made in one of the workshops of Tyre.[3] It is my favorite of the many lamps around the villa; it makes me feel connected to somewhere I’ve never been. I’ve heard plenty of stories about Tyre from merchants and travelers, but I’ve never journeyed more than a few days from home. What I wouldn’t give to see such a city!

When the child is finally asleep, I snuff the lamp and yawn. While I may dream of far-away cities tonight, tomorrow is a new day.

[1]Ameera Elrasheedy and Daniel Schindler, “Illuminating the Past: Exploring the Function of Ancient Lamps,” Near Eastern Archaeology 78:1 (2015), pp. 38.

[2] Elrasheedy and Schindler, pp. 40.

[3] John J. Dobbins in “Tel Anafa II,” II (2012), pp. 110, 130.

Before she was born, her parents got a wooden chair with glass inlays. The colors, green and yellow and blue, seem to glow. Her mother marveled whenever she sat on it – that she should go from being a farmer’s daughter to a merchant’s wife sitting on a seat fit for queens!

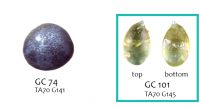

The little girl loves this chair, entranced by its beautiful hues. As glass starts falling off – the chair is old, and like so much in the villa needs an update – she picks up the prettiest piece she can find: a small oval, half yellow and half a light blue-green. Soon after, her parents replace the chair, and she forgets the old one’s colorful grandeur. This piece, however, becomes her favorite game marker, and she jealously guards it from her brother. She has never been to the sea, yet whenever she picks up her marker she imagines its colors.

The years pass. Just before leaving to marry a sailor, she looks through her childhood treasures. A pretty stone, an old comb – these she throws away. The glass counter she almost packs. But for what? She is grown now; she won’t be playing games on board.

Her brother’s wife just gave birth to a daughter, and her father’s siblings have new grandchildren. She decides to hide her small marker under the new chair. Maybe another little girl will find it, she thinks, and imagine the sea like I did.

Weeks later, she crosses a sandy beach, steps onto a boat and looks out to the horizon. Her first thought is that nothing compares to the real thing.

Katherine A. Larson, “Glass Counters,” in Tel Anafa II, iii, p. 137-144.

These alluring plaster fragments were found in Room 10 of the Late Hellenistic villa, where they had collapsed from the second floor dining room. The dining room walls were decorated in what is known as the “Masonry Style,” in which plaster was molded and painted to mimic the intricacies of expensive stone masonry. Appearing to be made of marble or granite, this style would have elevated the image of the villa’s owners. What is interesting about these fragments is that they display signs of re-plastering and repainting, showing that style mattered enough to the villa’s owners that they periodically remodeled. For them, style was a living phenomenon.

The variety of colors, patterns, and architectural features displayed in this room’s painted plaster reflects the fashionable world of the eastern Mediterranean in the later second-early first centuries BCE, and suggests the owners’ cosmopolitan outlook. Perhaps they traveled – to the Levantine coast, to Antioch or Alexandria – where they saw buildings with similar materials and designs that inspired them to commission something equally elaborate for their own home. When they entertained guests, conversation could have turned to the diversity of motifs and their far-flung origins; both host and company could take pride in their shared knowledge, and their ability to appreciate such fine things. These small bits of plaster are material emblems of a wide world in which keeping up with fashion and style showed that you belonged.[1]

[1] Benton Kidd, “Wall Plaster and Stucco,” in Tel Anafa II, iii, pp. 1-78.

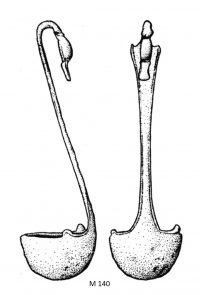

This bronze ladle was part of a wine service used at the villa at Tel Anafa. Its shape features a long handle that terminates in a duck’s head with a neck that curves over so that the ladle can be hung up. Additional details give this object personality. On the ladle’s deep bowl, two projections on either side of the handle base may mimic a duck’s wings. The handle narrows in the middle and again at the transition into the duck’s neck. The duck’s head is defined by two rings around its neck and a wide, flat bill. When hung upon the side of a serving vessel, the head remains visible so that the ladle acts as a decorative accent to the wine service. These details help turn a utilitarian object into an eye-catching accessory.

The most luxurious duck-headed ladles would have been made out of silver rather than bronze, although it is possible that this ladle’s surface was once gilded or silvered. While its material was not the highest quality, the attention to design speaks to “some pretension to luxury”[1] and suggests that the villa’s owner would have brought it out for special occasions.

[1] G. Merker in TA II, ii p. 245-246.

My Elissa,

The merchants are invading again. Your father told me to expect as many as twenty of them from Tyre for the marzeah.[1] Among them, I’m certain, will be that odious man who was here during your last visit—the one you said looked like an old wether, with his wooly grey hair and beard, splayed on the kline and bleating orders to everyone .[2] Remember how he scoffed at our wine service? That the strainer and ladle [3] were “pretty enough and nicely made, but in Pergamon they would surely be silver.”[4] What could he possibly know of the best dining rooms in Pergamon? He spends his days lurking around the stinking murex dye pots of Tyre.[5] Just for that, I will make sure he’s charged a dear price for our lower grade of thread. The girls have made themselves busy and we’ve a great store of filled spindles. With what I skim off the top, I could have the entire wine service gilded in silver—just to impress an oaf like him. Then, the next time he’s here, he might stop and wonder for a moment…”How they could have come into the money?” He’ll never suspect himself. I’m sorry for taxing you with my complaints, but your father can’t see through people like I do. And regrets for this short note—I must check on the kitchen girls. They have twenty patinas to produce for the coming mob. Come visit soon and bring the children!

Love, Mother

[1] Andrea Berlin, “What’s for Dinner? The Answer Is in the Pot,” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 6 (December 1999): 46–55.

[2] Barber, Prehistoric Textiles, 25–28.

[3] Merker in TA II, ii, p. 248.

[4] Donald Emrys Strong, Greek and Roman Gold and Silver Plate (Ithaca, N. Y: Cornell University Press, 1966), 90–93.

[5] Lloyd B. Jensen, “Royal Purple of Tyre,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 22, no. 2 (1963): 108.

To scholars today, terracotta lamps have value as archaeological objects whose date and origin can be identified by decoration and fabric. This one (L115), for example, is a mold-made lamp of a form known as ‘kite-shaped,’ which dates to the mid-late second century B.C.E. It is made of a grey fabric whose origin is likely the region of Tyre, on the southern coast of modern Lebanon.[1] In antiquity, however, lamps were valued for their function, meaning as sources of light. At Tel Anafa, excavators recovered 1,840 Hellenistic mold-made lamps, an impressive number that shows just how necessary these small, inexpensive objects were to those who lived and worked in the villa and its surrounding buildings.[2] When lit, a single-wick lamp like L115 would have cast about the same amount of light as two modern candles: perhaps enough to see one’s handiwork on a loom, certainly enough to shed a glow at the dinner table.[3]

Mold-made lamps were produced en masse, and many examples carried simple, even cursory designs. L115 is a bit more elaborate, with palmettes on the nozzle and handle, small S-shaped scrolls on the sides, and twin ridges incised with chevrons below the filling hole.[4] The lamp is essentially intact; only the upper portion of its palmette-shaped handle is missing. It thus remained usable, and it would be interesting to know how its ancient owner regarded it. Did she or he keep it, fond of its busy decoration, happy for the illumination it still could provide? Or – since there were ready replacements to hand – was it discarded as marred and so no longer worthy? It was, after all, a small object of cheap material, and there were many more in the villa’s storage room, even if not quite this fancy. A simpler vessel would still cast the same amount of light … and maybe dinner was waiting.

[1] J. Dobbins, TA II, ii, p. 141.

[2] J. Dobbins, TA II, ii, pp. 112-114.

[3] Ameera Elrasheedy and Daniel Schindler. “Illuminating the Past: Exploring the Function of Ancient Lamps,” Near Eastern Archaeology 78 (2015), pp. 36–42.

[4] J. Dobbins, TA II, ii, p. 141.

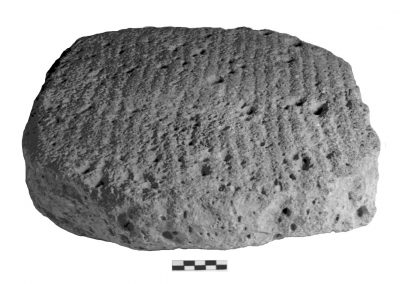

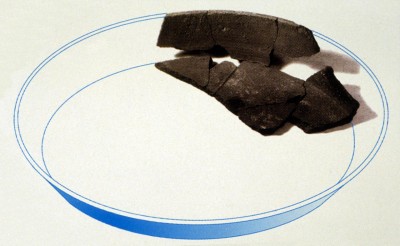

This lower grinding stone is part of the milling tool kit, a significant component of the bread-making process at Tel Anafa. Bread-making consisted of several steps: dehusking wheat, milling, and lastly making and baking bread. Upper and lower grinding stones were used as a set in the middle step, to turn wheat into flour. At Anafa, 41 upper and 13 lower grinding stones were found, almost all made from vesicular basalt. The stone’s pores helped to hold the raw grain in place, along with some water to smooth the process. Like the other lower stones, S44 is an elongated rectangle with rounded edges and a rough bottom. It has a flat work surface, which differentiates it from many other lower stones with a more concave shape.

All the grinding stones found at Tel Anafa are relatively small. This one is the largest of the 13 lower grinding stones found, at 44 cm long, 39 cm wide, and 5-8 cm thick. These dimensions may suggest that residents ground flour in small quantities, as needed, perhaps daily. From the total number of grinding stones recovered, it seems that the villa was a largely self-sustaining operation, something like a rural family farm today.

As undecorated, utilitarian objects, grinding stones and other handtools do not often receive scholarly attention. Yet their discovery gives us the opportunity to see firsthand how those in the past had to work for their bread. The grooves on the lower grinding stones allow us to imagine someone using them: bending over, pushing down on the hard upper stone and pulling it back and forth. S44, and other finds like it, remind us of the labor needed to produce basic foodstuffs in the past – and at the same time to cherish the ease we have today.

It’s time to prepare a sauce to enliven the wild greens we are serving at our midday meal.[1] I reach for my favorite grinding bowl, and set it on the table. The potter scored ridges into its lip, and my aging hands find its textured surface easier to hang onto than the smoother ones, which have more than once slipped out of my grip.[2] I put some garlic into the large shallow bowl, and then fresh herbs and spices, wincing as I accidentally scrape a knuckle against the bowl’s rough interior—perfect for grating things, but hard on the hands when I’m not careful.[3] Yet its roughness has served me well: on the inside, I’ve worn away the bowl’s reddish-gray surface nearly to the core.[4] It’s almost time to replace it, but I’m not ready yet. Taking hold of the bowl’s rim—the familiar feel of the ridges against my palm and thumb giving quiet satisfaction—I begin to crush the contents. The first passes of the pestle release a heady aroma of raw garlic and fresh herbs, and my stomach rumbles as I fall into a steady rhythm.

[1] Berlin in TA II, i, p. 123 notes that common uses for mortaria included crushing herbs and spices together and making sauces or dressings from garlic or honey.

[2] In a personal communication, Andrea Berlin noted that arthritis has been observed in the back and shoulders of ancient skeletons, likely a result of stress placed on the joints by prolonged use of grinding stones. While not direct evidence for arthritic ancient hands, the finding increases the likelihood of arthritis arising in other stressed joints, too, such as those involved in gripping. For a discussion of the probable importance of the ridged rim for an improved grip (Berlin in TA II, i, p. 125).

[3] Like other mortaria at Tel Anafa, this one too is made of an extremely coarse fabric with many inclusions, which impart “a kind of grater effect” to these vessels (Berlin in TA II, i, p. 123).

[4] Berlin notes that heavy use regularly resulted in thinned and sometimes worn-through vessels (TA II, i, p. 123 and the catalogue entry for PW 375, which reads “Interior worn through to core towards and at center”).

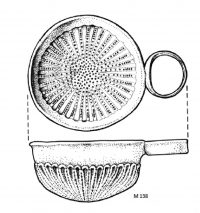

This pan is recognizable as having been made in or near Pompeii, in Italy.[1] The pan’s shallow height and flat bottom resemble a modern pie plate, making it ideal for baked dishes such as quiches or custards.[2] Ancient versions of quiche—called patinae—are listed on Roman menus from the mid-first century BCE, and an ancient Roman cookbook compiled by a writer named Apicius gives several different recipes for them. One such recipe made with asparagus could be made today:

“Put in a mortar the trimmings of asparagus which are thrown away, pound them, pour on wine and strain them. Pound pepper, lovage, green coriander, savory, onion, wine, liquamen [a type of ancient Roman fermented fish sauce] and oil. Pour the liquor into a greased dish and if you want stir eggs in over the fire so that it thickens, sprinkle with ground pepper. This is how you make a patina from wild herbs, black briony, mustard greens, or cucumber or spring greens. If you want, put a layer of fish or chicken beneath.”[3]

[1] Berlin in TA II, i, p. 104.

[2] Christopher Grocock and Sally Grainger, trans., Apicius: A Critical Edition with an Introduction and English Translation. (Blackawton, United Kingdom: Prospect Books, 2006), 16; Berlin in TA II, i, p. 104; Andrea Berlin, “What’s for Dinner? The Answer Is in the Pot,” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 6 (December 1999): 46–55.

[3] Grocock and Grainger 2006, 181.

Shell is among the first materials to be transformed into personal adornment. Naturally available and visually striking shell needs minimal work to transform it. In order for the shell above right to be made into a bead, a hole was drilled near the top, probably with a bow drill by hand, so that it could hang as a pendant. When worn, this bead, originally collected from the ocean or beach and brought inland, would have communicated status and connection to the world at large. It would have especially evoked the sea 30 km away on the other side of a mountain range. Of the 138 beads found at Tel Anafa only 13 were shell, which suggests prestige and rarity.[1] Today shell beads are considered humble, passed over in museums when displayed. Often shell beads are left in storage, thought to be too mundane for public interest. Yet we still collect shells from beaches and we still wear shells in our jewelry as a reminder of the sea.

[1] Larson in TA II, iii, pp. 117-118.

I finger the shell bead on a thong around my neck. Touching it reassures me. He said it would keep me safe when he left. I look west and brush at the hair the wind whipped in my eyes. Silly really, he is the one that needs to stay safe. Everyone else will be excited about the goods he brings with him back from the sea, the dye, the wine, the glass. But none of it matters. Not if he isn’t safe.

He said he collected it on the beach. Is he on that beach again?

My attention returns to my fingers tracing the ridges covering the shell. Beautiful. Not one of the shells used to make the expensive purple dye of course, but beautiful.

Mine.

A piece of him. It will keep me safe.

I let go of the shell and feel it fall against my skin. Mother is calling my name.

This Roman fibula, one of two of the Aucissa type found at Tel Anafa,[1] is a distinctive form with examples in collections around the world – although most are not on display. A fibula identical to this one, found in Cyprus and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (74.51.5562), is in storage, deemed unworthy for display. Objects move up or down in the hierarchy of adornment in museums based on the material that they are made of, the virtuosity of their construction, and their condition. Gold jewelry in perfect condition is at the top of that hierarchy. These fibulas are made of brass, a metal lower on the value scale. Yet such items were one of the most important pieces of personal adornment owned in the Roman era, as evidenced by their large size and, often, additional decoration.

After they enter a collection, ancient fibulas gain a second life as art objects rather than utilitarian adornment. This process is echoed by the fibula’s modern equivalent, the safety pin. Originally a pared down, mass produced item, the safety pin has been given new meaning in both the aesthetic and political spheres – picked up by contemporary jewelers and converted into art-jewelry, and also adopted as a symbol during the 2016 presidential election. These modern views may encourage us to re-connect with the layered meanings of the safety pin’s ancient predecessor.

[1] Merker in TA II, ii, p. 253.